By David Elfin

Washington Times Staff Writer

Sunday, July 16, 2000; Page A1

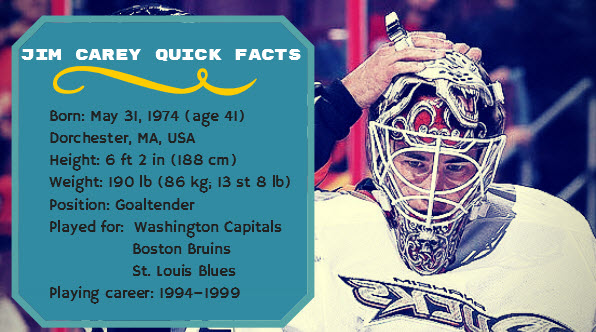

He was the best goalie in the NHL, the man who would be the cornerstone of the Washington Capitals for the next decade. He was talented, he was wealthy and he was barely 22.

Four years later, Jim Carey is a former goalie who doesn't want to pick up a stick again, stop a puck or hear the roar of the crowd. He lives in Florida and does not want to talk about the past. He is a mystery, a star that rose and fell with astonishing speed.

But in 1996 Carey's future appeared to be bright.

He is the only goalie in NHL history to be nominated for the Vezina Trophy -- given to the league's best goalie -- in each of his first two seasons. He won the Vezina in the second of those years, less than a month after his 22nd birthday. That summer, Carey wed his University of Wisconsin sweetheart, Stephanie. He had a dazzling smile and a game to match. Superstardom beckoned.

But when his former backup with the Capitals, Olie Kolzig, won the Vezina last month, Carey wasn't on hand to offer congratulations. The career of the player once known as ``Ace'' -- a nickname derived from a character played by similarly named actor Jim Carrey -- had come to a close in St. Louis the previous spring. Carey, the NHL's best goalie at 21, wasn't even offered a minor league contract at 25.

"Jim told me he had to get away from hockey, that it wasn't fun anymore,'' said Wisconsin coach Jeff Sauer, who also has sent star goalies Curtis Joseph and Mike Richter to the NHL. ``Things weren't going well, and he just decided that he had had enough.

"I think Jim left school prematurely [after his sophomore year], not so much from a hockey standpoint but from a maturity standpoint. Jim made a lot of money. Maybe things came too easy too quickly.''

Larry Pleau, the Blues general manager, agrees with Sauer.

"I've never seen a guy that young fall off so dramatically, so quickly,'' Pleau said. ``Maybe it was too much too soon. We put a lot of pressure on young people in our sport. Everyone was comparing Jim to [Pittsburgh's] Tom Barrasso when he got drafted, so he faced a lot of pressure coming in. But Jim lived with that and brought his game to a high level.''

Indeed, Carey, who went to the Caps with the 32nd pick (the first goalie taken) in the 1992 draft, couldn't have had a smoother ride to the top.

Carey turned pro in 1994 and was the American Hockey League's rookie of the year, going 30-14-11 with a 2.76 goals-against average for the Portland (Maine) Pirates before being summoned to Washington. The Caps, 3-10-5 when Carey arrived March 2, went 19-8-3 the rest of the way with the kid from Dorchester, Mass., claiming all but one of the victories.

The Caps blew a 3-1 series lead to the Penguins and lost in the first round of the playoffs as Carey struggled to a 4.19 GAA. His teammates didn't help him much; they scored just one goal in the final two games.

"Jim came to us at the right time,'' said then-Caps GM David Poile, who now holds the same job in Nashville. ``Our goaltending was pretty flawed, and he got us into the [1995] playoffs. His positioning was so good, it was like clockwork. But in the playoffs, Jim got moving east to west, and he was out of position a lot.''

Carey rebounded to capture the Vezina in 1996, leading the NHL with nine shutouts, winning a then-team-record 35 games and posting a dazzling 2.13 GAA. But Carey bombed again in the playoffs. The Penguins shelled him for 10 goals in 97 minutes (a 6.19 GAA), while Kolzig recorded a 1.94 GAA in the first-round loss.

"We put so much pressure in this sport on doing well in the playoffs, it's almost like what you did in the regular season doesn't matter,'' Pleau said. ``Jim didn't have the same kind of success in the playoffs. And when your team doesn't do well in the playoffs and you're the goalie, everything falls in your lap.''

When Kolzig, who had been drafted three years before Carey, finally showed he could handle regular work during the 1996-97 season, the Caps sent Carey to Boston in a blockbuster deal.

"The funny thing about that trade was that when David said he wanted [veteran goalie] Bill Ranford, I said we had to have a goalie back and David asked if I wanted Kolzig or Carey,'' Bruins GM Harry Sinden said. ``Of course, I went for the younger guy who had won the Vezina. Obviously, that wasn't one of my smarter decisions.''

Carey won the Vezina less than nine months earlier. However, Poile said making the trade that sent Carey and forwards Jason Allison and Anson Carter to Boston for Ranford and forwards Adam Oates and Rick Tocchet wasn't a hard decision.

"When we traded Jim, it wasn't under normal circumstances,'' Poile said. ``We were struggling, and we traded three good, young players for three veterans. You could already sense that the passion, the drive wasn't there in Jim. He was a nice person, but he didn't really integrate with the team. Sure, there are loners in hockey, but it just seemed that Jim didn't really want it. And you have to want it.

"Everybody has to deal with adversity. Olie dealt with plenty before he finally made it. Jim made it, and then he had to deal with adversity. You don't lose the talent that Jim had overnight. I think it comes down to Jim not wanting it badly enough. He didn't fight through the adversity the way we expected.''

Carey posted a solid 2.75 GAA for the Caps that season, but the trade threw him for a loop despite the fact that he was returning home.

"When Washington traded Jim, he was hurt,'' said Carey's agent, Brian Lawton. ``He felt he had done a good job for the Caps, that Washington was home and that he was going to be there for a while. He felt the trade was like someone was saying he wasn't good enough.''

Carey wasn't good enough the rest of that season in Boston, going 5-13 with a 3.82 GAA.

"We sold that trade on getting Jim,'' Sinden said. ``He was a local kid, and he had just won the Vezina the year before. Everyone in town was excited. When we got Jim, we thought there was a good chance that he could get back to where he had been. But he was pitiful in his first game, and by the end of that season after he played 18 games for us, I said to myself, `Wow. This guy can't stop anything.'

"Jim bore no resemblance to the goalie who had won the Vezina. He was flopping and diving and guessing. Everything was wrong. That was as big a dropoff as I've ever seen in a player. And when things didn't go right, Jim looked everywhere except at himself. He said we didn't have the right goalie coach. Jim said he wasn't used to a defense playing like ours, leaving him wide open. He just couldn't believe it was him. Jim was given a huge [$2 million] contract after just one full year. And the Vezina probably went to his head. It was like getting ready for games wasn't as important anymore, like he was thinking, `It's all over. I've made it.' ''

The Bruins traded for ex-Caps farmhand Byron Dafoe in August, and he beat out Carey in training camp. Carey played just 10 games in Boston and 10 for Providence of the AHL in 1997-98. When the Bruins and Caps met in the first round of the playoffs, Carey wasn't on hand.

"[New coach] Pat Burns came in, and he demoted Jim to second-string right away,'' Lawton said. ``It was like Dafoe was his guy and Jim wasn't. That was pretty upsetting to Jim because he felt it wasn't decided on the ice. Jim's a sensitive guy. No offense to Byron, who has played well for Boston, but Jimmy had been way ahead of him when they were both in Washington the year before. Jimmy hadn't been No. 2 since his third game in the NHL. He didn't believe he should be No. 2, and he wasn't being paid like a No. 2.''

Bill Howard, with whom Carey had worked in Wisconsin and who is perhaps his closest hockey confidant, said Carey's laid-back style grated on the old-school Burns.

"Pat Burns and Jim didn't get along,'' Howard said. ``Jim may not look like he's working hard in practice. People said that here about him, but Jim's idea of working hard isn't the same as some people's.

"Jim always produced. If a goaltender plays well, people should just leave him alone. Jim was happy about being traded to Boston, but then he bucked management. He wouldn't go to Providence at first. And that got 'em mad. Success didn't go to his head. Except for the playoffs and that one stretch in Boston, Jim always played well.''

Carey sparkled with a 17-8-3 record and 2.33 GAA at Providence in 1998-99, but the Bruins still released him March 1.

"Jim's stats might have been good, but that team was very good,'' Sinden said. ``We just didn't see any future for Jim. It wasn't one thing like Jim was playing too far back in his net and we could work on that. It was everything. When I told Jim that we were letting him go, it didn't bother him. That kind of confirmed what I thought about his desire.''

Carey washed out in a four-game trial that March with the injury-riddled Blues, whose goalie coach, Keith Allain, had been with Carey in Washington. And that was the end despite a career 2.58 GAA. Among active goalies with 70 career starts, only the incomparable Dominik Hasek and the last three Stanley Cup winners, Martin Brodeur, Chris Osgood and Ed Belfour, have lower GAAs. But Carey was unemployed.

"When Jim was with us, you could see his confidence was a lot lower than it had been in Washington,'' Pleau said. ``It was like he was putting himself through a wringer. We knew it was a gamble, but we were hoping Jim could find a place in our organization to give him a chance to re-find himself.

"Jim always had the physical ability. He was a big, talented guy. But you lose confidence and . . . I would liken it to a tennis player or a golfer. When everything's going right the shots are all falling in and the putts are dropping, but when they're not it's not easy to get that confidence back. Goaltenders don't have anybody to help them either. They've got to do it by themselves.''

Carey apparently didn't want to do that.

"Jim's a pretty intelligent guy with a lot of talent,'' Howard said. ``If he got himself in shape, he could play in the league in two months. But he told me, `I'm tired of people messing with my life.' Boston moved Jim out of that organization without giving him much of an opportunity, and St. Louis used him to get Grant Fuhr off his butt and back on the ice.

"The NHL is a little fraternity. The coaches and GMs are always moving around from team to team, and they gave Jim a bad rap. It's unbelievable that Jim's not in the NHL. But if you got jerked around for two years, you'd get tired of it, too.''

Carey got so tired of the games being played with his career that he had Lawton, a nine-year NHL veteran who was the top pick in the 1983 draft, decline all offers last summer.

"When the Blues said they couldn't keep Jim on their NHL roster after they had said they would, that might have been the final straw,'' Lawton said. ``Jim worked out a little bit that summer and then he told me, `I don't want to do this anymore.'

"I was getting a few feelers from teams, but they were all looking for a No. 3 goalie. I wouldn't have let that keep me from my passion, but Jim didn't have that instinct. He had other ideas about how he could spend his time. He went back to Wisconsin so Stephanie could finish her degree, and then they moved back to the Sarasota area.

"Jim made $800,000 or $900,000 the year he won the Vezina and then he signed a four-year, $11 million contract. And Jim has done so well with his investments that he doesn't have to work. He's working on his business degree at the University of Tampa and looking to get involved in the financial world. It's disappointing that Jim didn't persevere because he still had a lot to give to the sport. Despite everything that had happened, 24 was too young to leave hockey.''

Befitting his loner mentality during his playing days, Carey hasn't spoken to Howard or Sauer in months. None of his former teams knew his exact whereabouts. And despite encouragement from Lawton, Carey declined to be interviewed for this story.

Apparently the NHL's biggest mystery prefers to remain just that.